Of the absolute plethora of landmark examples of civil engineering that Ancient Rome offers, few give us as much insight about Roman life as their sewer systems.

While these systems were not the first sewers in human history (as humans have been digging permanent wells to find new and more sanitary water sources as long ago as 6500 BCE, and evidence of a primitive two-channel sanitation system separating fresh water and waste water was found in Skara Brae in Scotland dating back to 3000 BCE), they are some of the most well-known sewer systems throughout the world.

Rome is famous for the sheer scale with which all their architecture was implemented, up to and including their sewers. Throughout the Empire, Romans enjoyed the convenience of indoor latrines and plumbing that utilized a series of pipes and aqueducts to remove waste and bring in fresh water in to public fountains and wells. One of the largest and most complex systems was called the Cloaca Maxima.

Literally translating to Greatest Sewer, the Cloaca Maxima was originally built by the Etruscans as an open-air canal before the Romans covered over the canal and turned it into an underground sewer. While it did aid in creating more sanitary conditions, the Maxima was originally designed to aid in the removal of excess water from low-lying during floods. Its original construction was overseen by Etruscan engineers with large amounts of semi-forced labor made up of poorer Roman citizens. Later underground work is credited as being carried out by Tarquinius Priscus, Rome’s last king before the formation of the Roman Republic, around 600 BCE.

Studies of Rome, Herculaneum, and Pompeii have shown that Rome’s main goal in the construction of most sanitation systems was flood management and the removal of dirty water from areas where it would hinder cleanliness, economic growth, urban development, and industry. Despite this, it’s evident that the lauded Roman sewers provided less sanitary benefits than once thought. Many of them drained into the neighboring bodies of water that also doubled as the main sources of drinking water for their populations, and despite the large number of toilets in homes and public venues, very few of them appear to have been hooked up to the sewers. In Ostia, most private homes and a lot of apartment houses had single seat toilets that drained into what would have been rather pungent cesspits, the resulting waste was often sold to farmers or used in household gardens.

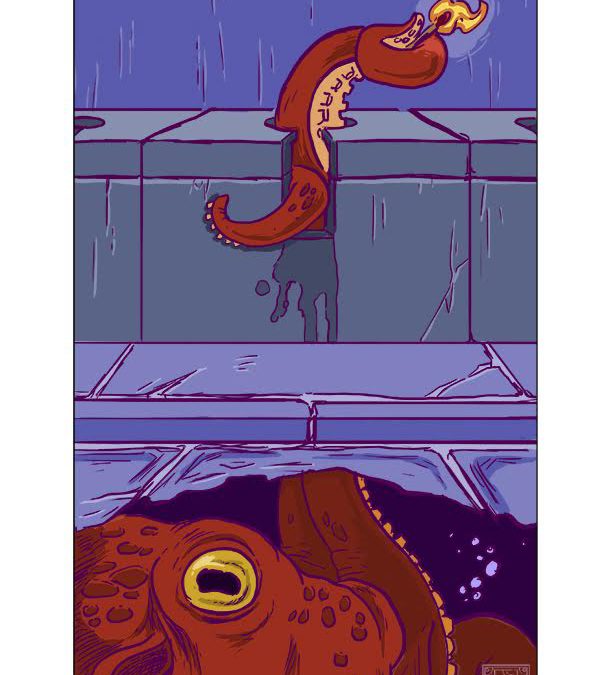

The cesspit toilets in public areas often were rather terrifying hazards that many owners of private toilets avoided. Reasons for such views stemmed from threats ranging from potentially biting vermin (like rats) and fiery emanations caused by gas explosions, due to build ups of hydrogen sulfide and methane. It is most likely that such scary encounters led to the superstitious tales of demons that often dwelled around such dank entrances to the underbelly of Roman cities. Such dangers are probably why the Goddess Fortuna is a common adornment in public lavatories, acting as a ward against demons and other dangers that come with not being able to hold your bladder until you get home in ancient Rome. In fact, graffiti in Pompeii dating back to ancient times was found warning public toilet users in no uncertain terms to “Beware the Evil.”

Ancient Roman records show that sewer hookups had no legal boundaries, so the question is why so few homes had them. The answer may be that Roman sewer openings didn’t have traps, making them entry points for all sorts of critters to enter one’s home. In fact, we have written documentation by the author Aelian (Aelianus). The story tells of a giant octopus that would apparently swim into the sewer from the sea and make its way up the drain to feed on the pickled fish in the pantry of a wealthy Iberian merchant in the city of Puteoli. Whether this is truth or fiction, it certainly gives a possible insight into why most private toilets were not hooked into the main systems.

Whether Roman sewers provided much sanitation or not, they still stand as a massive achievement in civil engineering. These systems allowed ancient Romans to manipulate the flow of water for the purposes of both waste removal and the transportation of fresh water, thereby allowing them to create cities on flood plains and settle areas miles away from major water sources using aqueducts and lead pipes.